Gentle Writing Advice

Courtesy of a poet and a playwright.

I studiously avoided looking at that “harsh writing advice” Twitter meme last week because lately I’ve been having such a difficult time getting any sort of writing done that I knew it would make me feel bad. Instead I took the opportunity to reflect on some of the gentler writing advice I’ve received or read over the years, which I will share with you now, a full week after the meme wrapped up.

The most formative piece of advice I’ve been given was also so obvious I’m embarrassed to call it formative. Years ago (not that many years ago) a visiting writer came to lead a poetry workshop I was enrolled in. When my turn came around, he looked at my poem and circled two sections of it. He pointed at one section and told me this was where I was trying to write a poem. He pointed at another and told me this was where I was saying something. You can probably guess which section was superior.

I consider this formative because it instantly reoriented the way I think about writing. Often when I sit down to write—a poem, an essay, what have you—my first instinct is that I want to write something good, an instinct I’m naturally inclined to satisfy by writing towards my preexisting notions of what “good” is. It’s normal and healthy to have these notions, but they can complicate the writing process if they compel you to make a thing that doesn’t exist in the shape of things that do. The problem with this approach—for me, at least—is that it circumvents the hard work of apprehending the true shape of whatever the new thing is. The final product can’t possibly be the most realized version of itself for the simple reason that it’s trying to be something else.

That hard work becomes much easier—again, for me—when I start by interrogating whatever urge I feel to say something. I use the word urge because this feeling is rarely clear or articulable: usually it’s a few words or a sentence I can’t get out of my head, a particularly strong emotion about something I’ve observed or experienced, even just an image from a dream that stuck with me long after waking. In each case the overwhelming sensation is that some untapped aquifer of subconscious thought is ready to be tapped. Usually I can only discover what exactly that thought is by getting out the first few words and thinking very hard about which ones should come next. It feels less like constructing a piece of writing than peeling away one that’s already there, like that old adage about the sculptor finding the statue in the block of stone. (Relatedly, whenever I have to actually outline and structure a piece of writing, it does not go well.)

We’re talking about content and form here, and I know it sounds like I’m saying that form—for me—proceeds from content. I don’t think that’s it, though; I think they’re wrapped up in each other. When that line “What is a metaphor?” popped into my head, I recognized it immediately as the refrain of a fairy tale; the next question was what came before and after it. When I wrote this poem, the first few phrases emerged with those breaths between them and I knew the whole thing would drift along in the same rhythmic, detached manner. If this is content unlocking form, it’s only because they share the same DNA.

Which is where the subconscious part comes in. What was so liberating about that writer’s critique—here’s where you’re trying to do it, here’s where you’re doing it—was that it taught me the most important part of writing is the one you can’t actually practice. You come up with things to say—things that need to be said—by living life. I’ve written about this before but it’s always worth repeating: you have to experience shit, feel emotions, read more than you can possibly write, formulate beliefs and politics, question and revise and even abandon them, have dreams and nightmares. It can take a very long time for the life part of the process to crystallize into something the conscious mind recognizes. The practice of craft helps us apprehend it more readily, but there’s no replacement for the long, slow act of being a human being in the world.

I suppose I’ve been dwelling on all this for the self-serving reason that I’ve found it mostly impossible to write creatively (and often non-creatively) for the last 12 months and I need the reminder that, well, obviously!, and that’s not a bad thing. But I also find it to be a useful framework for thinking about art, at least in that first step of trying to figure out why a given work does or doesn’t connect. It’s usually very easy to tell when a comedian has written what they think a joke should sound like rather than a joke that they alone can tell; ditto when a poet is trying to sound poetic. In my own practice I’m constantly asking myself whether my writing feels like writing or a person talking. That doesn’t mean I want it to sound “normal,” necessarily; people, like the world, are strange and rich and unfamiliar. It only makes sense that art should be too.

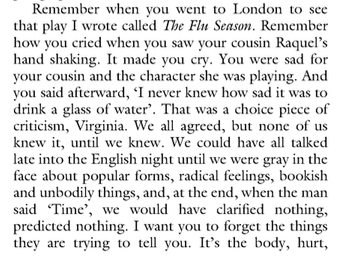

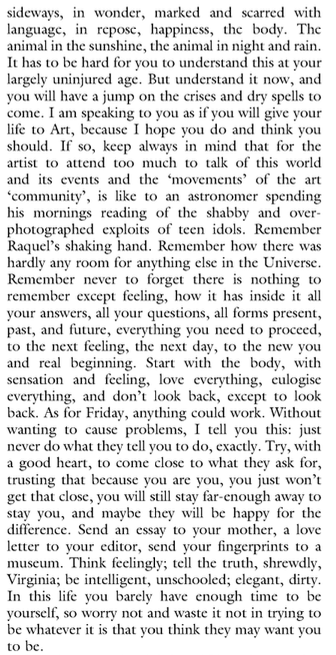

This brings me to the other piece of writing advice I cherish. It’s a short essay by the playwright Will Eno, structured as a letter responding to his niece’s request for input on a grade-school art project. The essay doesn’t exist publicly anywhere I can find; I came across it years ago when I had an academic JSTOR login, but I’ll email you the full thing if you want it. Here’s the section I keep coming back to:

I think I’ll leave it there for today.