Has Jimmy Fallon Done Anything Else Bad?

It's important to remember that stories like these are usually the tip of the iceberg, especially when we've already glimpsed the rest of the iceberg.

You probably saw Rolling Stone's investigation into the abusive work environment at The Tonight Show, which feels to me like an important shoe dropping. As I've written before, I think it's a safe rule that stories like these are the tip of an iceberg. When we hear about the bad behavior of powerful figures, it's usually because people in vulnerable positions have taken an enormous risk to tell us. On top of that, the stories that end up reaching us are only the ones that reporters can extensively corroborate. History and common sense suggest that abusers are rarely so considerate as to commit the totality of their abuse in a forum with witnesses and a paper trail.

Or to be a little blunter about it: there is obviously good reason no one associated with The Tonight Show, not even NBC itself, defended Fallon, who reportedly mustered the following apology to his employees today: "Sorry if I embarrassed you and your family and friends… I feel so bad I can’t even tell you."

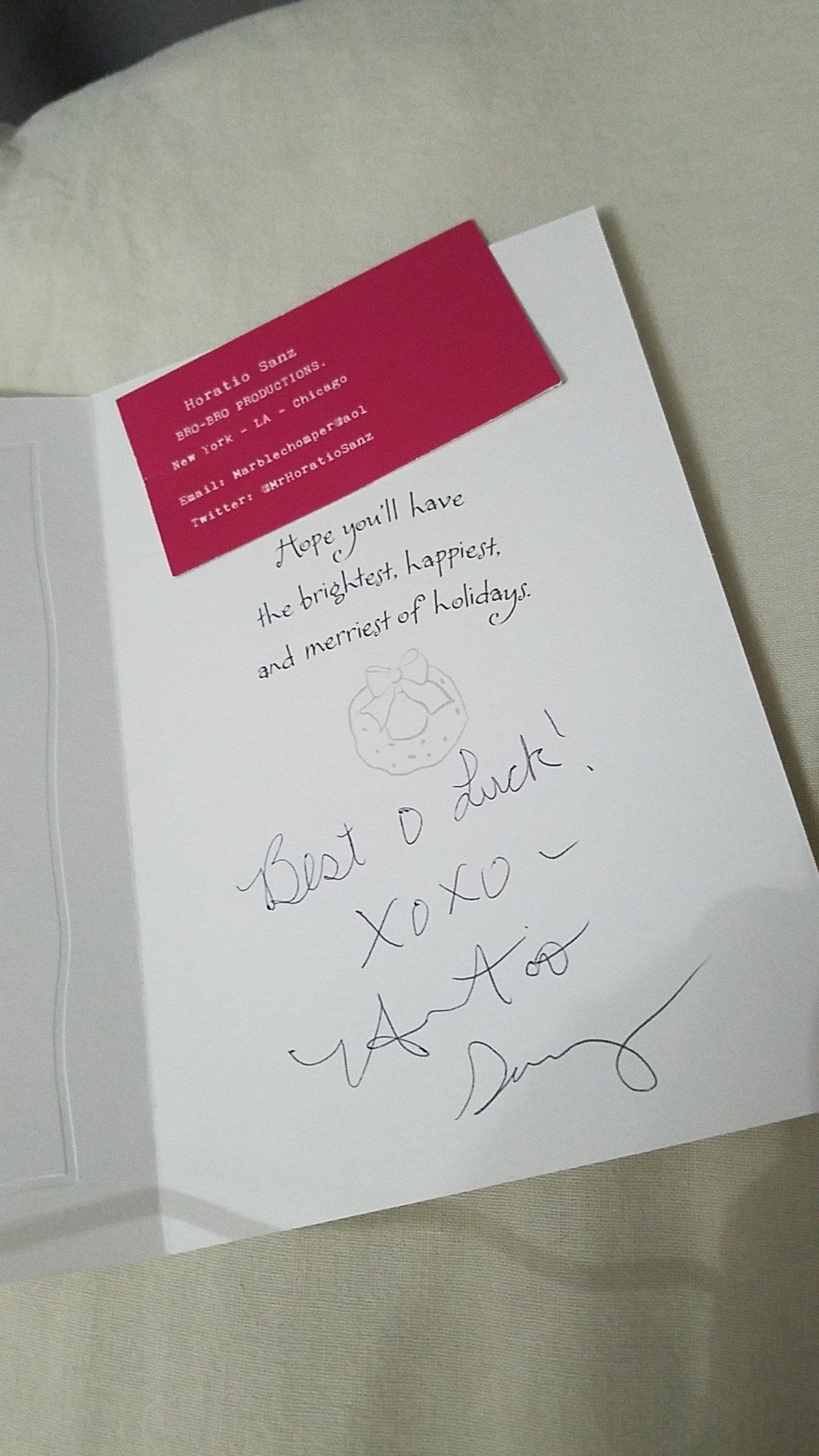

In the wake of this story, I'd like to use my little newsletter for something I've used it for too many times already: to remind the world that Jimmy Fallon was centrally implicated in the 2021 child sex abuse lawsuit against Horatio Sanz that settled last year. As you know, Jane Doe met Fallon and Sanz because she ran a Fallon fan site that gained their attention. When she was 15, according to the lawsuit, they emailed her from an NBC email address. Within a little over a year, she was hanging out with them at SNL cast parties, where she drank alcohol and chatted with the likes of SNL producer Mike Shoemaker, who would later produce Fallon's Late Night, and Lorne Michaels himself, to whom Fallon introduced her. Fallon, Sanz, and others around them all knew she was underage. Not one of these people have ever been asked about the allegations, which have been a matter of public record for two years now.

Okay: the world has been reminded. And now, one other thing:

It is funny to recognize that the end result of the abuse described in this report—and whatever else we don't know about yet—is a terrible unfunny show hosted by a shell of a man. We should all have a good laugh about this, about how pathetic it is that people like Fallon and his henchman sold their humanity for nothing of real worth. Then, I think, we should remember that the show isn't for us. It's for people obsessed with Jimmy Fallon, many of whom are teenage girls, just like Jane Doe was when she created a fan site in his honor. This has been The Tonight Show's primary constituency since the start. Fallon is certainly aware of this; he's even cultivated it. Let's revisit an email I received from a former FalPal in 2021:

For whatever reason, Jimmy Fallon's fanbase has always skewed younger. Like, predominantly teenagers and early 20s. His incarnation of Late Night ran from 09-14, and because the show utilized the internet more successfully than most others at the time, Twitter became the hangout place for his fans, the "falpals." (When I say fans, I mean people who have voluntarily watched Taxi more than once.) It was clique-ish; there were the falpals that had been to dozens of tapings because tickets were easy to get, there were the falpals who—like in the lawsuit—ran fanpages and managed to secure in-person interviews with him. (iheartjimmy.com or .net—I think they had both domains—was the big one. The woman who ran that, Lori, was probably in her 30s.) And then everyone else would try to make friends with those more elite falpals because it seemed like they had a bigger chance at access. As I'm typing this, I realize how fucking weird it was. We would livetweet every episode, play the hashtags game, follow all the writers, ask Jimmy to follow us. He did follow most of us, and it was that weird possessive internet thing where, the second a celebrity follows you, you think they're actually your friend and a real part of your life. Especially for the younger demographic. I was close to graduating high school at the time, so I was kind of in the middle of the pack. The people I've kept in touch with were all in their 20s/30s/40s, and everyone else was in their early teens.

I would comfortably say that everyone in that bunch got there because they were SNL fans. No one became a fan of Jimmy because of his role in Almost Famous, let's put it that way. There was one of Horatio's texts from the lawsuit that stuck out to me—something about how he was "stunted." Without getting into the semantics of that word or whether it's the best choice, it's a good shorthand for how we all got to this comedy fanbase. Late Night did some genuinely absurd bits during that time, like "Wheel of Carpet Samples," and that weirdness was a good home for a lot of people, the same way SNL has historically been a magnet for the weirdos and nerds and other folks on the fringes. And I suspect that's what made it so easy and alluring to people like Horatio and Jimmy—their job & the legacy of the network gave them a built-in, endless source of adoration and people who were either immature or just too young to know better. These are celebrities who literally had people sleeping on a sidewalk week after week for a chance at show tickets. That's a dangerously target-rich environment.

You may have gathered that I am concerned of late with the ramifications of celebrity. I think stories like the Rolling Stone feature show just how few people are actually served by fame, by which I mean Jimmy Fallon-levels of fame, the kind you get when you're regularly exposed to a national audience. Over the last few years, exposé after exposé have made clear how miserable these people are, and how consistently they pass on this misery to their employees. (Usually with the help of an intermediary layer of parasitic sociopath management-types, but that's another matter.) Other than a handful of corporate executives and their shareholders, it's hard to see who actually ends up happy in this system. The obvious response is "fans," I guess, but it seems pretty obvious that this whole dynamic is set up to exploit fans—whether in a more conventional consumerist sense (compelling them to buy stuff and have bad personalities) or by actually putting them in harm's way (see above).

At the same time, I'm not sure I believe the happiness of fandom is a good happiness. I think all the time about a passage in Sally Rooney's Beautiful World, Where Are You, in which the protagonist—a young, newly famous author—laments a viral tweet complaining about her boyfriend, who hadn't read her books:

At first I thought: a perfect example of our shallow self-congratulatory ‘book culture’, in which non-readers are shunned as morally and intellectually inferior, and the more books you read, the smarter and better you are than everyone else. But then I thought: no, what we really have here is an example of a presumably normal and sane person whose thinking has been deranged by the concept of celebrity. An example of someone who genuinely believes that because she has seen my photograph and read my novels, she knows me personally—and in fact knows better than I do what is best for my life. And it’s normal! It’s normal for her not only to think these bizarre thoughts privately, but to express them in public, and receive positive feedback and attention as a result. She has no idea that she is, in this small limited respect, quite literally insane, because everyone around her is also insane in exactly the same way. They really cannot tell the difference between someone they have heard of, and someone they personally know. And they believe that the feelings they have about this person they imagine me to be—intimacy, resentment, hatred, pity—are as real as the feelings they have about their own friends. It makes me wonder whether celebrity culture has sort of metastasised to fill the emptiness left by religion. A sort of malignant growth where the sacred used to be.

I had never thought of fandom in quite this way. Now it's the only way I can think about fandom. And not just fandom but also the huge machines that exist to sustain fandom, the tabloids and fan sites and stan accounts and rewatch podcasts and after-shows and awards shows and even the ostensibly respectable entertainment journalism that somehow still manages to treat the Jimmy Fallons of the world with kid gloves.

You can see its effects everywhere—in the way people talk about Fallon and John Mulaney and Joe Rogan, Johnny Depp and Taylor Swift and Elon Musk, all the podcasters and Twitch streamers they transform into a personality. The celebrity is friend and god at the same time. There's no critical distance, no space between imagination and reality, no room to see them as what they are: a stranger one doesn't actually know anything about. How can we ever wake up from a delusion like this?