A Few More Thoughts on UCB

And some news.

Hello!

I had a story out in Slate last week detailing UCB’s recent troubles and its possible futures. I am very excited to bring these issues before a wider audience. I am also fearful more bad news is around the corner. Earlier this week UCB laid off Alyssa Cohen, its LA-based Director of Human Resources, per internal sources who received an email announcing her departure. The LA theater’s Director of Finance and Procurement, Brittany Palensky, has left too. Finally, current and former employees tell me Alex Sidtis, UCBTNY Managing Director, has been let go, although UCB has yet to acknowledge it. When I called Sidtis last week to confirm, he said he was not at liberty to answer questions; UCB’s publicist did not respond to multiple emails.

If major changes are afoot, I suspect we will hear more about them after the Del Close Marathon this weekend. In the meantime I wanted to expand on a few threads in the Slate article that I think merit expansion.

Yes, It’s Discriminatory Not To Pay Talent

In the piece I quote David Mack, a Los Angeles theater administrator who’s spent years fighting for equity in small Los Angeles theaters. He told me: “When you’re making a choice to not pay the artists, you are actually making the choice to discriminate against people of color and women and people with disabilities.”

What he said next won’t shock anyone who’s been following this issue. But I think it is worth reiterating whenever possible: “If you have the opportunity to get an unpaid internship or an unpaid performing opportunity that may lead to another, maybe, later, performing opportunity, there's less likelihood that a person of color is going to be able to afford to take that unpaid opportunity than someone that's not. Because chances are they are working at least one job, or they're working two or three jobs or they have caretakers that they need to support, or they have discrimination that they're dealing with, so they're making less than their counterparts.”

“So if you're financially benefiting a company and you're not getting compensated for that, and you can't afford to not get compensated, then you're not going to be able to take that opportunity.” Mack said. “That's really a problem, especially for a performing arts community and performing arts leadership that prides itself on being so progressive—especially here in Los Angeles—and so democratic and valuing diversity so much and cultural equity. It really surprises me that they don't realize that they are complicit in and advancing, in my opinion, a systemically racist and sexist and ableist system.”

This is where pay intersects with the issues raised by Oliver Chinyere and Dominique Nisperos. Institutional racism, sexism and ableism cannot be staved off with free classes, sensitivity training and a human resources department alone in an institution predicated on free labor. Pay is essential to creating equity in the people teaching, the people on the teams, the people coaching the teams, and the people choosing all those people.

Theaters Like UCB Are Vital

One common response to my writing on UCB is that I “have it out” for the theater. I don’t. I think the theater is a vital part of the comedy ecosystem, one whose leaders don’t fully recognize that vitality. UCB is in a unique position to create a more vibrant, equitable, diverse industry; it has been in that position for more than a generation of comedians. But it has left the brunt of that work, systemic work, to individual workers.

Milly Tamarez is a New York-based UCB performer who co-founded Diverse as Fuck, an independent comedy festival highlighting underrepresented voices. DAF was born from a commitment by Tamarez and her co-founders to book only people of color on their shows. “It was so easy because no one was asking all these people; they would say yes immediately and confirm immediately and it would be a great show,” she told me. “So we were like, you know what? I bet you we could do a whole festival like this.” They did. It was a success, and will return this weekend.

Still, producing the festival is basically a second job for a group of comics who already have careers and dreams. “It’s not fair that for people who want to be seen onstage or want to see people like themselves onstage, they have to create a whole ecosystem of performances and workshops,” she said. “And I fear one day that it'll just be everyone building their own stadium, and then one day it's just going to be a street full of stadiums and we're not really working together to create something.”

There will always be a need for centralized institutions like UCB, at least so long as there are underserved artists without the time or resources to be their own managers (and bookers, publicists, mentors, etc.). Their value is not just in their stages but in their institutional knowledge. Late last year Nicole Silverberg, a UCB alum and late night writer, organized a series of free workshops for underrepresented comedy writers. They focused on what she described to me as “targeted training: what goes into a late night packet? How do you write monologue jokes or a headline script?” The workshops, held in February, were attended by 525 people, out of about 650 who originally signed up. “At the beginning of each workshop, I shared my philosophy: that when we reach a certain level of success we have a moral imperative to blow the doors open behind us and be transparent about how we got to that point,” Silverberg told me. “Information is not precious, and should not be hoarded. If having a famous parent or being an alum of the Harvard Lampoon isn't cheating, neither is telling someone that a monologue joke should end on the joke word.”

Like Tamarez, Silverberg said she does not have the bandwidth to run a larger and more sustained training operation. (Although she does plan to produce another round of workshops, and said she’d happily share her process with other organizers.) But the point is she shouldn’t have to: the transmission of institutional knowledge is the job of institutions. UCB does this job pretty decently for those who can cough up, say, $900 for notes on a pilot. Clearly there is a vast population of artists who cannot. It’s time for institutions like UCB to prioritize them.

How? Go Nonprofit

UCB is a for-profit limited liability corporation, even though its owners (purportedly) take no income from it. Were they to restructure UCB as a nonprofit, they could raise funding from public and charitable institutions, while reaping potentially substantial tax breaks. At an all-theatre meeting in December, the owners were asked why they don’t restructure. Their answer was twofold: Amy Poehler responded that converting from an LLC to a nonprofit would require them to “dismantle” the business, “which isn’t what we’re capable of doing.” Ian Roberts added that donors would impose creative restrictions. “You also run the risk of your content being controlled,” he said, which would undermine UCB’s mission as an alternative comedy theatre.

One point has more credence than the other. “It’s not that hard to convert an LLC to a nonprofit corporation,” Steven A. Bank, a professor at UCLA School of Law, told me. “But it’s not trivial and it could open up some issues depending upon the circumstances,” for instance if some debt is non-transferable without the lender’s consent.

As to Roberts’ point, you need only visit any nonprofit comedy theatre to see whether it’s truly a restrictive model. “I have never made a single change to the programming I’ve assembled because the board didn’t like it,” Allison Page, artistic director of the Bay Area nonprofit sketch theatre Killing My Lobster, which pays talent, told me. “As far as donor demand goes, I’m not aware that we’ve ever not done something because we thought donors wouldn’t like it. We try to do new work that challenges us in different ways as much as possible, and that’s what our audiences have come to expect, so they’re on board with that.”

David Mack, who has spent years in the nonprofit theatre world, believes grant-givers would be eager to support a theatre like UCB provided it pays talent. “There are a lot of major donors who would be very attracted to these types of companies, and who stay away because they don't know if their money is going to be spent well,” he said. “And how can you blame them when they're not even aware of what the law is, much less be in compliance with it?”

This is not to suggest going nonprofit would solve all of UCB’s problems. Far from it. UCB’s cultural issues, including its owners’ perverse view of their labor force, transcend any particular business model. There are plenty of exploitative nonprofit theaters; there are fair and sustainable for-profit ones. But I think in UCB’s case, conversion to nonprofit status would be an important first step toward sustainability. It would open up avenues to vast resources UCB could use to address its many other problems, such as the need for its training center to subsidize the theater. The removal of a profit incentive would allow writers and performers to make risky work for less-than-sellout crowds. And it would enable the theater to make money without doing branded shows like “The Lyft of Gab: Rideshare Conversations,” which strike me as wholly antithetical to its mission.

Why Does This Matter?

There is one former UCB performer I spoke to, Joe Hartzler, whose story starkly illustrates the industry-wide radiations of UCB’s labor practices.

For many years there was a steady pipeline from UCB to digital comedy sites like Funny or Die, College Humor, Super Deluxe and Above Average. This pipeline has lately dried up as these companies, whose work is generally not governed by union rules, contract or vanish. In its infancy, Funny or Die recruited staff writers from UCB, who farmed their contacts for unpaid acting talent. “As the younger generation at UCB, if anyone with seniority asks you to be in a Funny or Die sketch, you drop everything to do it,” recalled Hartzler, who once had a speaking role in a political sketch that got hundreds of thousands of views without paying him one cent. Funny or Die eventually implemented day rates, and cheap appearances would occasionally lead to more lucrative union commercial work—a compelling reason to keep doing the cheap stuff.

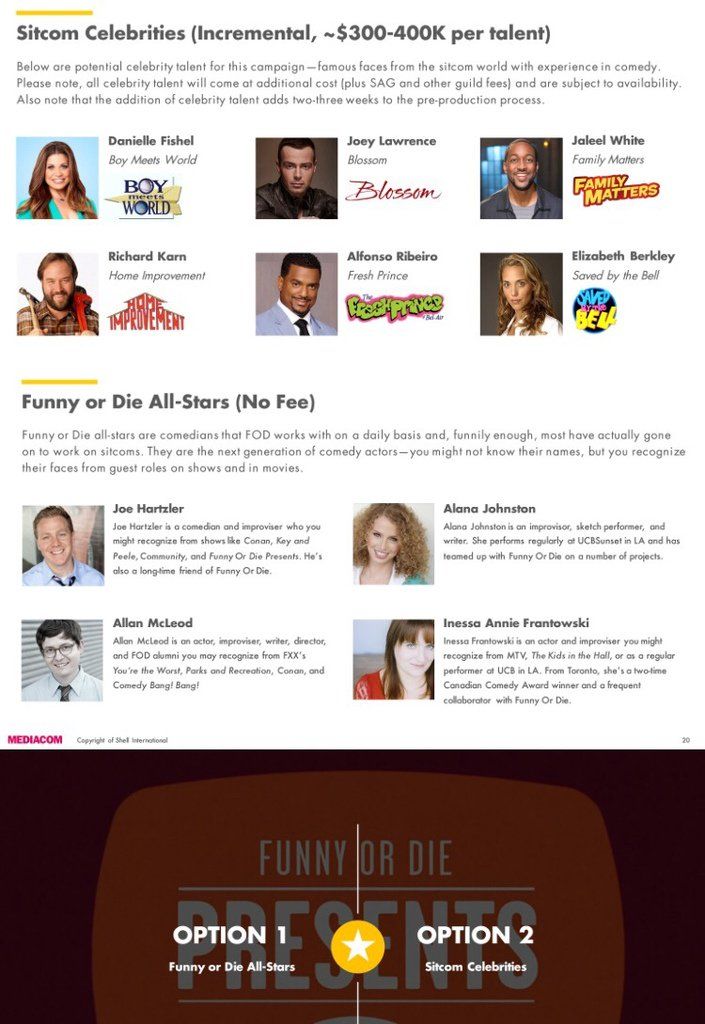

One day, Hartzler recalls, “Funny or Die got caught passing around a sales deck. It was a card with images of eight different actors. On the top half of the card were four celebrities from 90’s sitcoms. It listed their fee as $300,000-$400,000. Then below the celebrities were four more actors. They were labeled, ‘Funny Or Die All-Stars.’ My picture was one of the four listed… I was free. If they wanted Urkel, it’d be [almost] half a million dollars. If they wanted me, I was free. Worthless. This was my reward for playing ball.”

Funny or Die

Years ago Hartzler made several unpaid appearances on improv4humans, Matt Besser’s podcast. He had to sign a release giving Earwolf ownership of whatever he improvised. “In the early years it was fine,” he said. “I figured I was paying my dues, lucky to be there. I got to improvise with Amy Poehler.” A while after one appearance, he learned from a friend that Earwolf had repurposed his appearance—his voice, his improvised material—into an animated short without notifying or paying him.

More recently Hartzler accepted a role in a new media company’s web series, only to learn on set that it was also a Chevy commercial. “I was getting paid a garbage rate,” he said. “I didn’t walk off set and I’ve regretted it every day since.” Some time later he was invited by a “famous comedian” to perform in a sketch. When he received the script days before the shoot, he discovered it was sponsored by Amazon Visa. “I emailed the producer and the famous comedian and apologized,” he said. “I regretted to tell them I couldn’t do the Amazon Visa script for $150.”

Hartzler’s experiences point to a bleak truth about the modern comedy business. Where there is paying non-TV/film work, it is often because some massive brand is paying for it. Yet somehow very little, if any of that money goes to talent. (In 2015 EW Scripps bought Earwolf’s parent company for $50 million; Earwolf has only recently begun paying podcast guests.) Increasingly, the TV work is little better: I spoke to one performer who recently auditioned for a SquareSpace commercial and a TVLand demo, both non-union.

To say what goes without saying, this is a system whose doors open primarily to those who can afford to work for free or cheap. Like UCB, it is also a system that discriminates on multiple axes. This matters because the fight for equity in the bigger ecosystem starts in smaller ones. UCB could teach its workers to value their labor; it could teach them to demand what they’re worth, to walk off sets that don’t meet their demands; it could close its considerable mailing list to potentially exploitative casting calls, rather than simply saying “Don’t Be Exploited” at the top of each email. It could pay them for labor.

But it doesn’t do any of this. Instead it teaches its workers that all these exploitative practices are normal. It tells them they are not worth anything until opaque market forces opaquely decide otherwise. It tells them they’re on their own.

They don’t have to be.

Header image via Travis Wise on Flickr.

Hello! Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this, please consider sharing it. This newsletter is free for the time being, but any support you can offer will go toward more comedy industry news and analysis. Comments, tips, corrections, and other stray thoughts are always welcome here or on Twitter, where my DMs are open. Bye bye.